Much like most of you: I love grammar. I love the structure of a sentence and taking it apart. I consider myself to be the "King of Parsing" - I can easily tell you about a word in a particular Latin sentence, giving you everything (and more) about its form and function without even thinking - it just seems to roll off of my tongue. As Latin was taught in a grammar-translation fashion when I was in high school and in college, this is why I loved the subject - it came very natural. NOTE - I am still shocked that I was planning to major in Sports Medicine at UCLA.

But let's be honest: grammar is not language itself. To quote Kato Lomb, a self-taught polyglot: "One learns grammar from language, not language from grammar." That does not mean that grammar does not have its place, but just not the HUGE, OVERARCHING, EXPLICIT and ALL-ENCOMPASSING place which we have given it in the past. As my dear friend Donna Gerard has said, “Grammar is not one of the 5 C’s” (referring to the 5 C’s of the ACTFL Standards for 21st Century Language Learners).

The grammar-translation books from which most of us learned Latin had the paradigm chart at the beginning of the chapter with a lengthy explanation of a particular grammar topic. Next came a list of somewhat random vocabulary words. Following that were even-more random sentences using the vocabulary and grammar in order to get in some practice. If we were lucky, there was a short story to read in Latin (I do not ever remember reading stories in the Jenney book when I was in high school). We spent time in class conjugating verbs and declining nouns aloud, writing out synopsis of verbs and parsing isolated words for their possibilities. We learned songs to memorize our noun declension endings. For vocabulary quizzes, we wrote out the dictionary entries for the nouns and all four principal parts of the verb. To us, this was Latin. As 4%ers, we loved it. But 96% of our own students do not, as it has no bearing in their lives.

When one gets right down to it, is it really important for students to know grammar, as in being able to name that the verb is 3rd-person, plural, imperfect, subjunctive, passive used in a relative clause of characteristic, if they understand what that word means in that context? In math, is it truly important for students to know the term additive inverse if they understand how to do that particular math problem?

But shouldn’t students know grammar? I heard at ACTFL this past November that parents have 100% success rate in teaching language to their children and that they never teach explicit grammar to them. You will never hear a parent say to their 2-year old child, “It looks to me like you have mastered the use of the present tense, so let’s move on to the imperfect tense. You are now ready to start talking about an event which has happened in the past but yet is either habitual or is in motion at the time of discussion.” Parents simply speak to their children in understandable, contextual messages and pattern language for their children to mimic. Essentially, that is what we should be doing with our students.

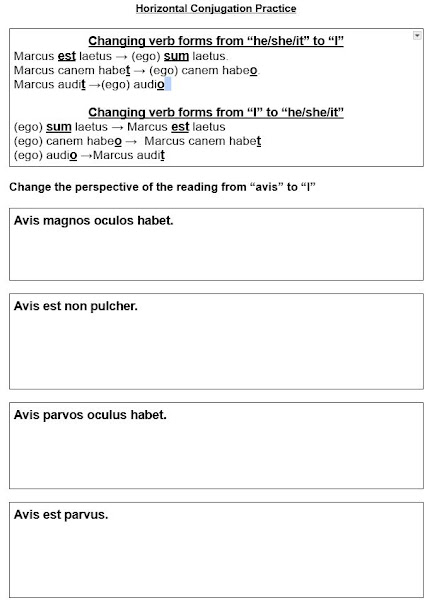

So how does one teach grammar in a Comprehensible Input classroom? Let’s dispel a myth by establishing that grammar is indeed taught in a CI approach; it just is not the centerpiece of a lesson. Just introduce a new grammar concept in an obvious, understandable way.

This is how I taught present participles (stage 20 CLC) last semester:

Day 1 - Dictatio where present participles were used in a story, but the meaning was obvious based on the context. Students wrote out the sentences in Latin as I dictated it to them, and afterwards, if they did not understand the meaning of a word or form, especially a participle, they asked, and I told them the meaning. Following the dictatio, we did a group translation in English of those sentences and quite honestly, many were able to translate the participle correctly due to the context. I never said the word participle nor got into an explanation of the form.

Days 2-3 - TPR and TPRS storytelling where present participles were used. In TPR, an example:

Teacher: O Joseph, bibe aquam (Joseph begins to drink the water).

O discipuli, videtisne Josphem bibentem aquam? (ita).

Ita, videtis Josephem bibentem aquam. O discipuli, videtisne Josephem bibentem an consumentem aquam? (bibentem)

Ita, videtis Josephem bibentem aquam. O discipuli, videtisne Josephem consumentem aquam? (minime)

Minime, non videtis Josephem consumentem aquam. quam ridiculum! videtis Josephem bibentem aquam. What do you think bibentem means? (drinking). Yes, bibentem means “drinking.”

In a TPRS story, this time, I wrote the participles on the board with their English meaning and pointed to the words whenever I used them. I circle-questioned the participle form in order to get in repetitions. Over these two days, students started to catch onto the form based on context and sounds; acquisition was subconscious due to the amount of repetitions. If a student asked about the -nt- or -ns, I explained that it meant “_____ing” but I did not make a big deal about it.

Days 4-5 - As a class, we read through a short story where present participles were used. I read through it aloud first, while I acted it out. Again, I wrote the participles from the story on the board along with their English meaning and pointed to them when they were used. We then did a read/discuss in Latin and then did a read/draw. Following that, the class did a timed-write in Latin of that story. Still no major discussion about participles.

Day 6 - Word Chunk Game, where many of the sentences had present participles in them but the meaning was obvious based on context.

Day 7 - As a class, we read through another short story where present participles were used. Finally, I began to do short 30-second “grammar timeouts” in English and explicitly brought attention to the -nt- or -ns and told them that it meant “_______ing.” - I said “Whenever you see a word wearing PANTS, that means “______ing.” This was done for those students who need explicit explanations (in reality, I have found that many of these types of students have already figured it out but they just want explicit confirmation). So as we continued reading, I took a time-out, saying something like “”Hey, this word is wearing PANTS - what does that tell us?” or “How did we know to saying running and not ran or was running? Yep, it’s wearing PANTS!” Although I now use the term participle, I do not use the full term present active participle. I just do not think that it is necessary.

Day 8 - micrologue story involving present participles.

By the end of the chapter, students were pretty familiar with present participles, and I never had to create a worksheet for them to practice the structure. Have they mastered the present participle yet and are able to use them? Not at all - as language acquisition is a spiral and not linear in fashion, that will come over time as they experience more of these forms in context.

So university Classics departments and College Board AP Latin folks: asking students to know labels and parts of speech explicitly is not language itself. Grammar is not one of the 5 C’s